The universal language of connection

April 25, 2022

*The following article includes quotes that were translated from Mandarin Chinese by fluent speakers on the Hoofprint staff. Though every measure was taken to ensure accuracy, the translated materials could contain differences in meaning and syntax when compared to the source.*

Jason Xu

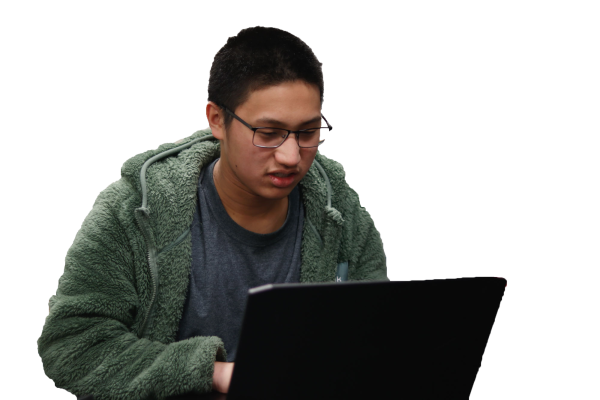

Senior Jason Xu’s first month of attending Walnut High School was dominated by two emotions: frustration and loneliness. He was completely unaware of what the new environment demands of him—having no access to Google Classroom, missing a student identification number, being unaware that Aeries Parent Portal even exists. Yet, the most daunting part was the dread of knowing that he was alone in his troubles. He felt that he had no one to consult for help, which left a mountain of problems before him.

Compared to his first month at Walnut High School, Xu’s previous life back at Shanghai Shangde Experimental School in China was vastly different. Xu felt that his old school was much more direct, as he was simply placed in one class the entirety of the school day. Since Walnut High School requires students to take on more responsibilities, such as setting up student accounts and locating classrooms on campus, Xu found it challenging to adjust to the new system, especially considering that the language barrier hindered his ability to ask for help.

“You’re anxious. You don’t know everything that is going on here. Sometimes you don’t even understand the teacher’s instructions,” Xu said. “Everything comes so fast, but you have to adapt to it.”

To his surprise, Xu gradually received help from Chinese-speaking students, who helped him adjust to the new academic and cultural scene at Walnut by guiding him through the school day. However, Xu felt that solely talking to people who spoke the same language created a social bubble, which encouraged him to begin talking to others around him, Chinese-speakers or not, to break out of that bubble. He joined Associated Student Body (ASB) in his junior year, enabling him to work on projects, such as creating posters, with other people and expand his social group.

“There are two kinds of friend groups. The easiest way for kids to find a friend group is to find students who speak the same language, but [it’s easy to get] stuck in that bubble forever,” Xu said. “The second way is frustrating, just [trying] to speak with everyone else. Slowly, you will get over it.”

Moving from a familiar community in their native land to one in the United States is oftentimes an uncomfortable and sometimes terrifying transition for English learners. Because they feel that they are not completely familiarized with the culture within the Walnut community, they find solace in finding a way to connect with the people around them. They actively seek out aspects in high school that resemble aspects of their previous life, whether it’s by establishing social groups or by joining organizations on campus.

“If you want to build a relationship with other students, there’s always a way,” Xu said.

Jenny Guo

Watching the horrors of the pandemic and racism against Asians unfold on the news, sophomore Jenny Guo makes the subconscious decision to speak Chinese quietly on the streets, concerned over the idea that people are listening to her. The thought of the sheer magnitude of the situation brings about the question of whether she should keep her thoughts to herself and appear invisible to be more secure outdoors.

“It’s like when you go to a bank and withdraw money: it’s your responsibility to safeguard that money so no one steals it from you,” Guo said. “I think it’s the same thing; it’s so that I can protect myself. Even if no one comes and does these things to me, these protective measures at least make me feel more secure.”

However, while attending Walnut High School, Guo found that there were a lot of Chinese students enrolled, which freed her from the troubles of masking her Chinese identity. Finding people who spoke the same native language fluently alleviated the pressure of adjusting to a new environment, as she formed a friend group that she felt comfortable socializing with. Amid the pandemic, Guo took every opportunity to socialize, scouting out other Chinese students in her class. By adding them via WeChat, she was able to create a friend group during distance learning. It is through speaking the same language that Guo is able to connect with others.

“When you enter a very new, large collective, it’s natural that you try to find something that you know,” Guo said. “I think all Chinese people understand this — first you find a friend group or collective and then you try to branch out.”

The ELD (English Language Development) program is one way that students such as Guo find others who speak the same language. In an effort to mitigate the difficulties brought up by the language barrier, the ELD program places the English learners into designated classes that focus on improving their English speaking skills. Student performance in the class as well as on the English Language Proficiency Assessments for California determines their level, ranging from 1-3, in the ELD program. Because ELD students are placed in a class regardless of their level, the ELD classroom environment helps to establish a comfortable and familiar learning environment for English learners.

“The most important thing to me is that they take ownership of their education and learn to love or come to appreciate having the privilege to learn a lot,” ELD coordinator Rebecca Chai said. “Learning is such a thing that’s taken for granted everywhere. I do hope that they come to appreciate their educational opportunities.”

Kelly Lin

Back in Zhongshan, China, senior Kelly Lin followed a packed academic schedule. The blaring alarm started off her day at 6:30 a.m. That meant 45 minutes left until morning reading. After morning reading, the first block of classes of the day started, ending at 12 p.m. A short lunch break offered a brief breather from the academic scene, but the next block didn’t end until 5 p.m. To complete all the assigned homework, Lin knew that she’d have to stay at school until 10 p.m. before allowing herself to go home.

Attending one of the top middle schools in her region, Zhongshan No. 1 Middle School, Lin found that the academic scene was rigorous. Consequently, when Lin first entered Walnut High School, she found herself with a less academically inclined schedule. With school ending at 2:45 p.m. and teachers assigning less homework compared to her teachers back in China, Lin found herself with more free time. The Walnut High School environment struck Lin by surprise, as it created a culture that was different from her old middle school, whether it be recreational activities or how students behave on campus.

“Living in a new environment is something that is fresh and more difficult for me. I heard about the differences between China and the U.S. such as living conditions, eating new foods and being involved in a new education system,” Lin said. “But I have never thought that there are so many things. ‘Free’ is the main word that I can conclude about life here. There are not many rules to obey. You could wear what you want without being required to wear a uniform, or being able to change your hair colour as you please — I can’t do these things when I study in China. Though I can show my personality freely, I still prefer such rules in China because I think students at school should have a student-like appearance.”

Chinese-speaking English learners generally come from a school that is more academically oriented and thus feel that Walnut High School is less strict. However, this does not necessarily mean the learning environment is more easygoing or undemanding to them.

“In the United States, there is a sense of urgency since there are so many people that are better than you. Even if your parents do not hover over you, and you don’t do it yourself, you would feel as if you should be doing something more,” Guo said. “In China, there’s this feeling where everyone is supporting and protecting you on your way to the top, and you step by step get to college under their wing. Here, there are less people competing, but you must want to succeed.”

Xin Chen

Having a strong passion for music, senior Xin Chen attended a music-focused middle school known as Xiamen Music School in Xiamen, China. While spending half the school day attending general classes such as math and science, Chen spent the other half practicing the cello. Coming from Gulangyu, nicknamed Piano Island for its piano music and talented musicians, Chen was surrounded by people that he could readily contact for resources.

However, Chen moved to the United States amid his sixth grade year to Stanley G. Oswalt Academy in Walnut, which forced him to transition from a musically-oriented environment to a less specialized school. At Oswalt, Chen was placed into the ELD program, which prevented him from joining the orchestra because it took up space in his schedule. As such, he found that he had lost a lot of his musical resources from moving to the United States because he was forced to spend his time learning English and assimilating to American culture instead of practicing music. Though Chen joined the orchestra in Walnut High School, he felt that the classroom environment did not match his experience back in China. Chen’s transition reflects that in order for English learners to move to an American school, they must sacrifice some aspects of their previous life.

“I’m playing seriously. I want to go to college for music. There’s not many people that decide to become a professional musician, or I haven’t been able to find anyone that has the same thought like me. Maybe there are people, but I’m just not comfortable speaking in English with other people so I can’t find [these kinds of people]. I feel alone in this music environment,” Chen said.

Ellen Chang

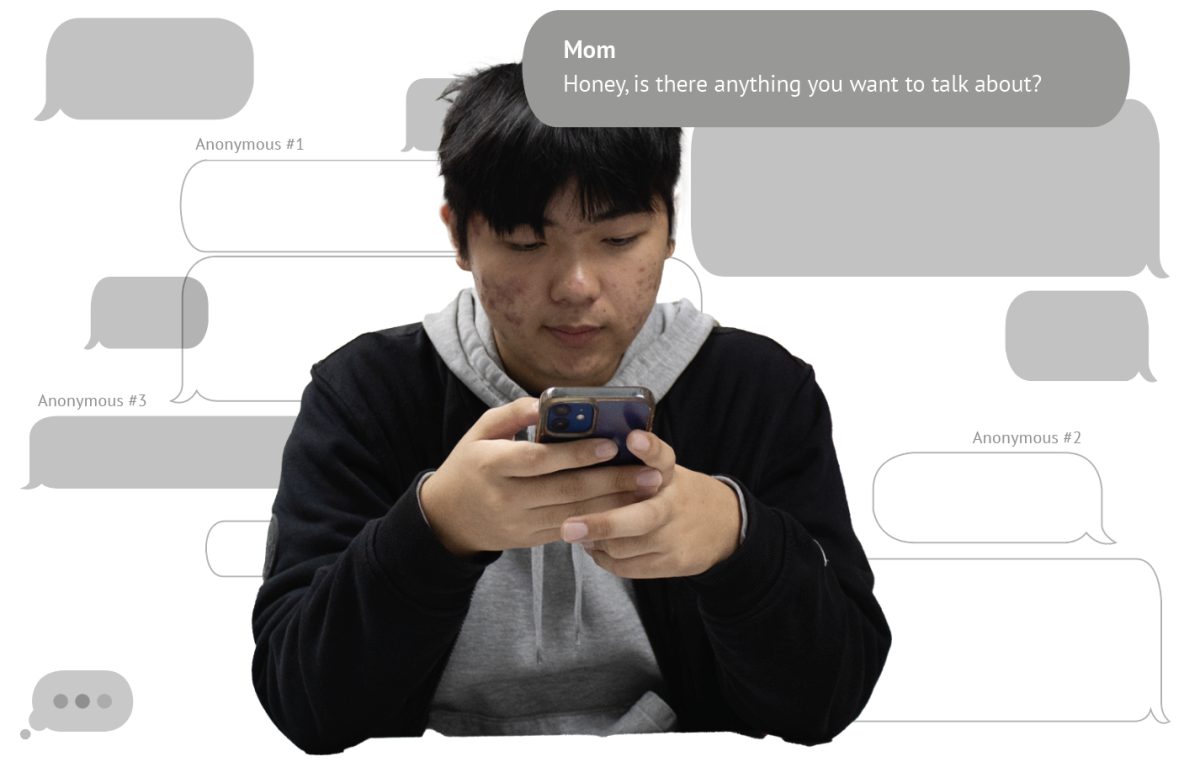

Reflecting back on the hours she spent trying to understand the assigned homework or processing the information written in the textbook, former ELD student senior Ellen Chang realizes one important thing.

“I wish I had a tutor. You really wish there’s someone next to you that could help you translate and help you understand that subject,” Chang said.

Chang now dedicates time to helping ELD students succeed in their own classes as one of the leaders of the International Community Club. Through a buddy system, she guides an English learner through academic assignments, helping them pronounce and write words in English. Chang was placed in the ELD program for two years after coming back to the United States from Taiwan. Though she felt comfortable in the ELD environment, classes such as science and history posed a challenge for her, as these classes required knowledge of more advanced vocabulary. Remembering the struggles of trying to understand a subject, Chang felt the need to help out students who experience the same difficulties.

“If [ELD students] really need my help, I would give all my time to them. It’s because I went through what they’re going through,” Chang said. “I want them to be more successful and I don’t want them to go through the hardships that I had. I want to make it so that they enjoy what they’re learning.”

Like Chang, several upperclassmen who were previously involved in the program actively help out English learners who are not fluent in English. They engage in friendly conversation that encourages ELD students to practice speaking in English. This is done in an effort to alleviate the language barrier, as it helps the students adapt to the predominantly English-speaking environment instead of forcing them into it.

The reason I really want to help the people around me is because I understand their feelings,” Xu said. “I’m still struggling with the language. I want them to understand that even though they don’t speak perfect English, that they can still communicate with the people around them.”

Janina Jiang

As a member of Chamber Singers, senior Janina Jiang shares her enthusiasm of singing her favorite songs—an expression of her musical passion. She feels that the musical environment is her second home, offering a place to learn English and make friends.

Performing as a Chamber Singer marks the culmination of Jiang’s three years of dedication and determination. Jiang began her choir journey in her freshman year as a Mustang Singer, the introductory course in the choir program, not only out of pure interest, but as an opportunity to improve her language speaking skills. Captivated by the melodious sounds created by upperclassmen in more advanced choir levels, Jiang committed herself to staying in the program. Her decision to do so reignited her passion that had been present in her previous life in Shanghai, where she participated in her church’s choir every Saturday. Additionally, the choir program provided her with an opportunity to expand her social group.

“The most important thing is we can sing there — sing a lot of songs, sing the songs we love,” Jiang said. “Choir is a good place to practice English and make friends. When I first joined choir, I didn’t have friends [in choir] because I was not so good at English. But the people tried to talk to me about how my day was; people were very welcoming.”

Organizations such as arts programs or student-led clubs provide a way for English learners to find a group of people that share the same interests, or discover an outlet for them to incorporate aspects of their previous lives to their current one. For example, choir director Lisa Lopez, with the help of Chai, invites ELD students to choir to encourage English learning alongside music making.

“I just hope they can find a home [through choir],” Lopez said. “If they just came from another country, this will be a lot to absorb. I hope it’s somewhere where it’s a place to make friends — a place to do more than just schoolwork.”

With sacrifice, English learners optimistically look toward the future. Completing the high school curriculum provides them with the opportunity to seek a higher level of education in the United States. Specifically, English learners aim for American colleges in hopes of acquiring a job with a well-paying salary. Though, like any other high school student, they are unsure of what to do beyond college, they have hope that they will be able to figure it out.

“I want to provide them an environment where we encourage them to ask for help,” Chai said. “If you could imagine, in most Asian countries, it’s the sage-on-the-stage lecture type of work that they’re doing. School hours run so long in those countries, and they have a different view and a different idea of what education is. In that respect, I think we’re teaching students to basically stand up for themselves and advocate for their own education.”

![Sophomore Francesca Chu and junior Mary Mora work on a project to rebrand a portion of UNICEF’s social media. “We have a pretty big team doing this, which makes things a lot easier,” Chu said. “[The project’s] going pretty well; we’re about to wrap up and I’m excited to see how the representatives will react to the work.”](https://whshoofprint.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Screenshot-2024-02-12-at-11.31.22-AM-600x446.png)